Interview with Ratchapoom Boonbunchachoke (Useful Ghost): "I found the idea of a ghost possessing an electrical appliance fascinating!"

- culturasiamomiji

- Aug 25, 2025

- 8 min read

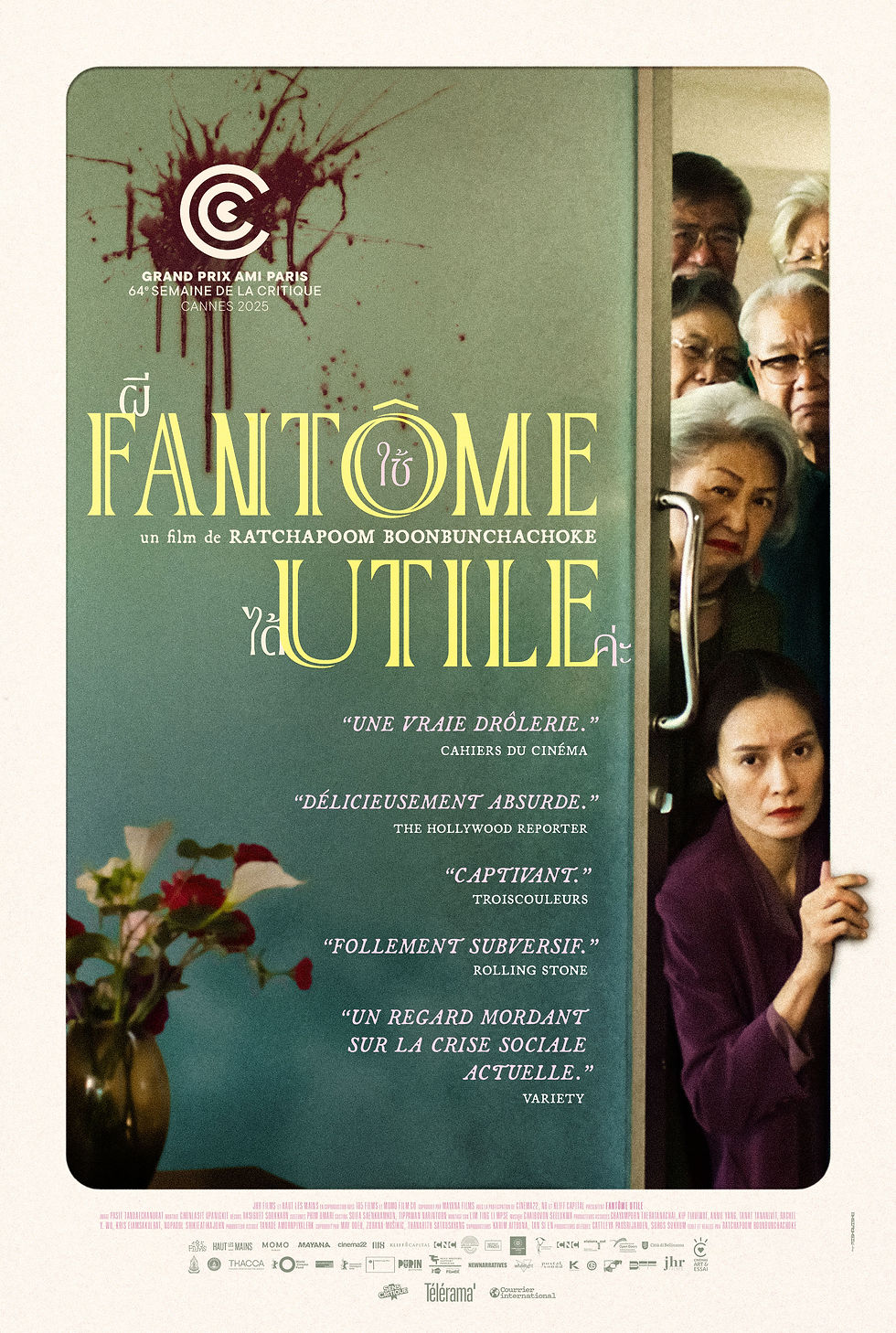

Useful Ghost, the first feature film by Ratchapoom Boonbunchachoke, made waves at the latest Cannes Film Festival by winning the Grand Prize at Critics’ Week, a section dedicated to showcasing emerging filmmakers. Building on this reputation earned on the Croisette, the film has just been selected by Thailand to represent the country in the “Best International Feature” category at the upcoming Academy Awards in the United States. We’ll have to wait a little longer to find out whether it will make it onto the final shortlist...

On August 27, Useful Ghost will be released in French theaters. And it’s safe to say you’ve never seen anything quite like it, judging by its synopsis alone: After the tragic death of Nat, a victim of dust pollution, March sinks into grief. But his world is turned upside down when he discovers that his wife’s spirit has been reincarnated in a vacuum cleaner. Absurd as it may sound, their bond is rekindled, stronger than ever—though far from universally accepted. His family, already haunted by a past factory accident, rejects this supernatural relationship. Trying to convince them of their love, Nat offers to clean the factory to prove that she is a “useful ghost,” even if it means cleansing the place of wandering souls...

Completely unexpected and offbeat, Useful Ghost will make you laugh far more than it will scare you. But far from being a mere comedy, Ratchapoom Boonbunchachoke’s film also probes the history of Thai society, its hidden wounds, and their consequences. The ghosts we bury, like the dust we try to ignore but that always resurfaces.

We had the opportunity to ask the director a few questions about the genesis of the film.

You were selected at the latest Cannes Film Festival for the Critics’ Week. How did it feel when you first heard the news, then to arrive on the Croisette? And finally, to win an award?

Every stage of development brought both joyful excitement and anxiety. Before knowing about the selection, I was nervous. Then I was overjoyed when I heard the news. However, I became nervous about how the film would be received in Cannes—would audiences like and welcome the film? Yet, winning the award reassured me greatly. It was one of the best days I have ever had.

Was France a valuable support in the production of your film?

Absolutely! Without the funding from CNC—Cinema du monde, making the film would have been impossible. With the support of the French grant, we were able to complete the film as we had wished! I can't thank them enough.

You revisit the myth of the ghost in cinema, which has been widely explored around the world and in Thai culture. Were you inspired by any particular works?

My primary inspiration came from Mae Nak Phra Kanong, Thailand's most enduring ghost legend. This 19th-century tale has been adapted countless times across every medium—film, television, theater, comics. The story is about a woman who dies in childbirth while her husband fights in war. When he returns, he's overjoyed to reunite with his wife and child, completely unaware they're both dead. The neighbors, horrified by this unnatural relationship, eventually call in a monk to banish her spirit.

What fascinated me in this story was the idea of a forbidden relationship between the living and the dead. Then I had this other image that kept haunting me—a ghost walking through a modern office building, not to scare anyone, but simply to work. This image reflects the reality we live in, as these are such difficult times that even the dead need to work to make a living.

These two ideas—the forbidden relationship between a human and a ghost, and the ghost who needs to work—became the foundation on which I slowly built the story.

Why did you choose electrical goods to “embody” your ghosts? How did you work on the conception and selection of these objects for the film?

I researched the cinematic history of ghost representation and discovered various approaches filmmakers have used over the decades. In early films, ghosts were often depicted visually—as translucent figures or floating beings without feet. But what really caught my attention was the 1980s American tradition of poltergeists, where ghosts remain invisible yet communicate through manipulating household objects: switching TVs on and off, moving furniture, opening windows.

Moreover, I found the idea of a ghost possessing an electrical appliance fascinating. In a way, it makes such a strong statement about our current time, where people are reduced to being objects or instruments which are merely used for their functions. Their humanity is lost and replaced by pure utility.

For the selection, my main criterion was whether the objects looked funny and adorable on film.

The cast features very popular Thai actors such as Davikah Hoorne as Nat and Apasiri Chantrasmi as Suman. How did you manage to convince them, and do they look at their vacuum cleaner differently since the shoot?

I think both of them might have wanted a bit of an adventure after working in the industry for years. I suppose, for Davika, after so many successes in more mainstream roles, she might have wanted to venture into uncharted territory. She was eager to try new things, and playing a haunted vacuum cleaner is very new, I guess. As for Apasiri, she's a well-respected veteran in the industry. I'm really not sure why she took on the role, but I'm so delighted that she joined our journey.

Your film is marked by its many shifts in tone: sometimes comedic, with the first appearances of the vacuum cleaner, more down-to-earth when such a ghost’s presence seems completely normal for some characters, and far more dramatic as the story progresses. How did you manage to juggle these different registers?

Throughout the filmmaking process, I stayed committed to the emotional truth of my characters. As a filmmaker, I believe you can experiment with different cinematic styles and techniques, but ultimately, it's the characters that audiences connect with. Your film can constantly transform into as many new shapes as you want, as long as audiences are engaged with the characters.

To be honest, I wasn't consciously thinking about tonal shifts because I was always focused on the same core relationships and emotional threads. The tone of a film would naturally vary throughout the story, but as long as the audience are emotionally invested in the characters, the tonal variations feel organic rather than jarring. If viewers follow the characters’ journey through the entire film, then I feel that I've done my job.

Dust is a recurring element in the film, right from the opening shot. It represents both the deceased and the “nobodies.” Could you tell us more about this?

In Thailand, 'dust' can be used as a metaphor for people who are treated as less than human—subhuman—like when people say 'our government has been treating us like dust.' You have no power and your voice can't be heard. Also like dust, you're so small and insignificant in the eyes of those in power. They can do whatever they want with you—sweep you, move you away, or get rid of you. For me, 'dust' is such a powerful figure which coveys several layers of meaning, especially for those who understand Thai culture.

Through some of your previous short films (which we would love to discover!) and Useful Ghost, you also explore Thailand’s political history and the universal notion of the duty of memory. Do you see this as your duty as a filmmaker as well?

Honestly, I don't think of it as a conscious duty. How I view my commitment to cinema can vary from film to film. Though right now, I'm drawn to using cinema to explore the more forgotten parts of history, I don't think I would confine myself to doing just that.

Cinema is uniquely powerful because it's a collective medium—it brings people together in a shared space to experience stories. That makes it an ideal platform for confronting viewers with marginalized voices, minor histories, and overlooked narratives that might otherwise remain buried. But film is also incredibly versatile. It can be anything.

As I evolve as a filmmaker, my interests will probably shift too. Maybe I'll move away from historical themes entirely and explore something completely different. And that's okay.

Your film also includes several homosexual characters, more or less accepted by their relatives. That’s quite a sharp perspective: Thailand is also very well known for its numerous boys’ love series, openly progressive and ahead of their time, even before same-sex marriage was legalized. Is this a subject you also feel strongly about addressing?

My main goal is to expand the narrative possibilities for queer characters. Too often, LGBTQ+ people in cinema are relegated to stories that revolve entirely around their sexuality or coming-out journeys. While those stories matter, I found it limiting—as if queer people can only exist in one type of film, discussing one aspect of their lives.

Why can't queer characters be in action, political thriller, or social satires? I didn't want to make another film 'about' being queer—I wanted to create a film exploring socio-political issues that features strong queer characters.

Is the fear of forgetting also one of the reasons why the film appears in a slightly “aged film reel” look, as if the image could burn away at any moment?

Aesthetically, I'm fond of the grainy texture of film because it reminds viewers they're watching something constructed—it emphasizes cinema's artificiality rather than hiding it. But the aged, deteriorating look serves another purpose too.

I wanted the film itself to embody the ephemerality of memory. Memory is fragile and fleeting—it's not going to last very long. Even the medium that we use to record memory, celluloid, is vulnerable to deterioration and decay. I found it very poetic to use a dying medium to tell a story about ghosts and forgetting.

Your film is also visually striking, whether through the choice of sets (such as the electroshock room) or the costumes and their colors. For example, Nat shifts from the red of the vacuum cleaner to the blue of Suman’s factory workers. Suman, on the other hand, is always contrasted with the colors worn by her family (green). Could you tell us more about this?

I love artificiality. I love how a film keeps reminding audiences that they are watching something constructed and composed. As an audience, I also love realistic films, but as a filmmaker, I'd go in another direction. As everyone knows, poetry is poetic because it is so different from how people actually speak in real life. Nobody speaks in rhyme! So, as I envision my film as a form of poetry, I exploit the opportunity to create a new world where colors, shapes, and forms can be creatively choreographed and composed. It's pleasing to watch.

Ironically enough, the ghosts seem far more alive than the other characters themselves: they are often stoic, framed in static shots. Suman’s empty gaze is also highly evocative…

I think most of the ghosts in the film are angry, while humans are more desensitized by their living.

Useful Ghost will be released in French theaters on August 27. Would you like to shoot a film in our country?

Of course! I already have an idea for a story that would partly take place in France.

Do you already have other projects awaiting you?

I already have my fourth film in mind. Making a film takes time, so I want to start as soon as possible. For my next film, I want to make an adventure film.

Interview conducted via email. Words translated and edited by Gabin Fontaine. Many thanks to director Ratchapoom Boonbunchachoke for his availability, to the JHR Films team, and to Célia Mahistre and Cilia Gonzalez for making this interview possible.

Gabin Fontaine

Comments